Dockerfile

Using existing docker images unfortunately only gets you so far. Especially, when you need to put models into production, it is very likely that you will need to encapsulate more logic within the image itself to integrate it in your existing processes.

In this section, you will learn the basic building blocks for generating docker images.

By convention the instructions for a docker image are stored in a text file called

Dockerfile (full reference).

This is not set in stone, so you can name it anything you like. However, it is usually best

to stick with the conventions that a community expects (just like with

PEP-8 in the Python community).

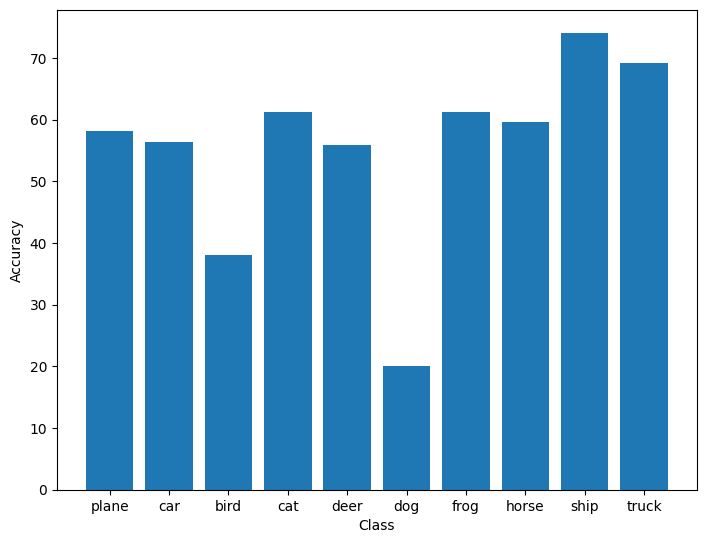

In order to make this section not just a hello world example, we will build an image that we can use for training and evaluating a PyTorch model on the CIFAR10 challenge. The Python script will also output a Matplotlib bar chart, displaying the accuracies of the classes.

Each of the following sections will introduce a docker command that will make up the final docker script for creating the image. Of course, we will also build and use the image, as well as push it out to make it publicly available.

Comments#

Before we dive into the actual docker commands, a quick note on comments. Just like with

any other programming language, it pays to comment your instructions. Especially, if you

need to work around quirks with some strange command-lines. Comments in docker files,

like with bash programming, are line comments and start with #.

FROM#

Docker images (just like ogres) are like onions, consisting of multiple layers. This makes it easy to add more functionality to existing images: reusing is better than recreating. This approach also preserves a lot of space.

The first (non-comment) statement in your Dockerfile needs to be the FROM statement, which tells docker the particular base image on top of which you want to build.

Reusing the image from our pull command in the Basics section, we get the

following initial statement:

FROM pytorch/pytorch:1.6.0-cuda10.1-cudnn7-devel

ARG#

In some cases, your Dockerfile script might need to be parametrized for the build from

the outside. For defining such a build parameter (with a default value), you can use the

ARG instruction. Using the

--build-arg command-line you can override the default value.

The ARG syntax is simple:

ARG key=value

You can also use ARG to make your FROM statement easier to read, but be aware of the

interaction between FROM and ARG.

Using ARG, we can pull out the version numbers from our original FROM statement and

put them in variables. Variables can be used in other statements via ${...}.

Here is the human-readable FROM statement:

ARG PYTORCH="1.6.0"

ARG CUDA="10.1"

ARG CUDNN="7"

FROM pytorch/pytorch:${PYTORCH}-cuda${CUDA}-cudnn${CUDNN}-devel

ENV#

In contrast to ARG, the ENV

instruction is persistent within the docker image and can be used to set environment

variables rather than build variables. If the variable should not be persistent in

the final image, as it might interfere with subsequent layers, then you should

consider using ARG instead.

One such environment variable is DEBIAN_FRONTEND, which changes the behavior of

apt-get (Debian tool to install packages):

ENV DEBIAN_FRONTEND=noninteractive

The docker documentation on the ENV command lists alternative ways of specifying such an environment variable, for limiting the scope.

In the Interactive timezone prompt section section, you read why you might want to use this variable.

RUN#

Once you have set the stage with base image and variables, you can set about installing

the required software packages. For Debian/Ubuntu based systems, this usually involves

invoking the apt-get package manager and for Python pip/pip3. Executing commands

is achieved with the RUN command.

For installing matplotlib, which is not part of our base image, we can use:

RUN pip --no-cache install matplotlib

You will notice the --no-cache flag, which is not something you would normally use.

In order to avoid downloading the same library over and over again, pip caches them

by default. This is not necessary for a docker image and just takes up more space.

But before you argue that you could just remove unwanted files at the end of your

docker image then you do not take into account that docker works in layers:

every command is basically a layer. Though a subsequent layer may remove files (and

you will not see them in the final image), they are still present in the layer that

they got introduced in.

Long story short: either always clean up within the same layer or avoid generating temporary files altogether.

Check out the following Best practices sections:

COPY#

Quite often, you will end up just needing little scripts within a docker image

to do the work for you (since all the libraries get installed via apt-get or pip).

For copying files or directories, you can use the COPY

command.

One thing that we have not talked about yet is the docker context. This context

includes all the files and directories that are on the same level as the Dockerfile.

The COPY command can only use files and directories that are within this context,

but not outside (e.g., going up in the directory structure).

You also need to be aware that the complete docker context will get sent to the docker daemon during the build process. So best not to have any unnecessary files and directories in the same directory. However, if it cannot be avoided for certain files/directories to be present you can use the .dockerignore file to exclude them.

As mentioned at the start, we want to train a PyTorch model and evaluate it.

Download the test.py script and place it next to

the Dockerfile that you are currently working on.

In order to include this Python script, use the following command:

COPY test.py /opt/test/test.py

The COPY command will automatically create directories if they are not present,

which is /opt/test in our case. Any existing file will get overwritten as well.

Not only Python scripts can be copied, you can also create executable bash scripts

that call your actual Python scripts and place them in /usr/bin. For our test.py

the bash script would look like this:

#!/bin/bash

python /opt/test/test.py

If your script supports command-line options, you can pass them through using "$@":

#!/bin/bash

python /opt/test/test.py "$@"

WORKDIR#

With the WOKRDIR command,

you can change the current working directory within your docker script. If the directory

does not exist yet, it will get created automatically. This eliminates the need

to use mkdir commands. In our case, we can just use the command to make the

docker container automatically start the prompt in the directory of our Python script

(/opt/test) when used in interactive mode:

WORKDIR /opt/test

Other useful commands#

Building the image#

With our Dockerfile now finally complete, we

are ready to kick off a build. After changing into the directory containing

the Dockerfile, you can use the build sub-command to perform the build.

Rather than using a hash, we can give it a name via the -t option (tagging it):

docker build -t pytorchtest .

You should see similar output like the one below:

Sending build context to Docker daemon 260.6kB

Step 1/8 : ARG PYTORCH="1.6.0"

Step 2/8 : ARG CUDA="10.1"

Step 3/8 : ARG CUDNN="7"

Step 4/8 : FROM pytorch/pytorch:${PYTORCH}-cuda${CUDA}-cudnn${CUDNN}-devel

---> bb833e4d631f

Step 5/8 : ENV DEBIAN_FRONTEND noninteractive

---> Running in 71812ab36f5a

Removing intermediate container 71812ab36f5a

---> 77a27d586581

Step 6/8 : RUN pip --no-cache install matplotlib

---> Running in 10d85cc41a73

Collecting matplotlib

Downloading matplotlib-3.4.2-cp37-cp37m-manylinux1_x86_64.whl (10.3 MB)

Collecting kiwisolver>=1.0.1

Downloading kiwisolver-1.3.1-cp37-cp37m-manylinux1_x86_64.whl (1.1 MB)

Collecting cycler>=0.10

Downloading cycler-0.10.0-py2.py3-none-any.whl (6.5 kB)

Requirement already satisfied: pillow>=6.2.0 in /opt/conda/lib/python3.7/site-packages (from matplotlib) (7.2.0)

Requirement already satisfied: numpy>=1.16 in /opt/conda/lib/python3.7/site-packages (from matplotlib) (1.18.5)

Collecting python-dateutil>=2.7

Downloading python_dateutil-2.8.1-py2.py3-none-any.whl (227 kB)

Collecting pyparsing>=2.2.1

Downloading pyparsing-2.4.7-py2.py3-none-any.whl (67 kB)

Requirement already satisfied: six in /opt/conda/lib/python3.7/site-packages (from cycler>=0.10->matplotlib) (1.14.0)

Installing collected packages: kiwisolver, cycler, python-dateutil, pyparsing, matplotlib

Successfully installed cycler-0.10.0 kiwisolver-1.3.1 matplotlib-3.4.2 pyparsing-2.4.7 python-dateutil-2.8.1

Removing intermediate container 10d85cc41a73

---> 0361d66c3c44

Step 7/8 : WORKDIR /opt/test

---> Running in 14568b3fead5

Removing intermediate container 14568b3fead5

---> 7c1a8b7229d0

Step 8/8 : COPY test.py /opt/test/test.py

---> ed55c4fb8e62

Successfully built ed55c4fb8e62

Successfully tagged pytorchtest:latest

Running the image (interactive)#

With the image successfully built, you can now use it. For this you need to employ the RUN command.

docker run --gpus=all -v `pwd`:/opt/local -it pytorchtest

Once the prompt appears, you can execute the test.py script:

root@5e2245aa020a:/opt/test# python test.py

While the script is executing, you should see output like this:

cuda:0

Downloading https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar-10-python.tar.gz to ./data/cifar-10-python.tar.gz

100%|██████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████▉| 170369024/170498071 [00:13<00:00, 13670749.69it/s]Extracting ./data/cifar-10-python.tar.gz to ./data

Files already downloaded and verified

[1, 2000] loss: 2.173

[1, 4000] loss: 1.815

[1, 6000] loss: 1.659

170500096it [00:30, 13670749.69it/s] [1, 8000] loss: 1.557

[1, 10000] loss: 1.499

[1, 12000] loss: 1.449

[2, 2000] loss: 1.377

[2, 4000] loss: 1.356

[2, 6000] loss: 1.329

[2, 8000] loss: 1.315

[2, 10000] loss: 1.293

[2, 12000] loss: 1.264

Finished Training

GroundTruth: cat ship ship plane

Predicted: cat ship car plane

Accuracy of the network on the 10000 test images: 55 %

Accuracy of plane : 60 %

Accuracy of car : 65 %

Accuracy of bird : 29 %

Accuracy of cat : 44 %

Accuracy of deer : 54 %

Accuracy of dog : 41 %

Accuracy of frog : 52 %

Accuracy of horse : 68 %

Accuracy of ship : 78 %

Accuracy of truck : 63 %

170500096it [01:16, 2240182.93it/s]

At the end, the script will generate a bar chart plot and save it as /opt/local/figure.png:

If you look at the permissions of the generated image, you will notice that the owner

is root. Depending on your permissions on the host system, you might not be able to

remove it from outside the container. One approach is to change the owner using chown

(from within the container), but that can become tedious. Instead, see the following

Best practices section on how to best address this:

Congratulations, you have assembled, built and run your first docker image!

Running the image (non-interactive)#

Of course, you do not have to run the image interactively at all. After the initial development of your docker image and code, you can then use it in your production system.

For running it in non-interactive mode, simply remove the -it flags and

append the command that you want to run. In our case, this is:

python3 /opt/test/test.py

The full command-line therefore looks like:

docker run --gpus=all -v `pwd`:/opt/local pytorchtest python3 /opt/test/test.py

Optimizing an image#

As a final note, you should consider revisiting your Dockerfile once you have

verified that everything is working and optimize it. Optimizing entails:

- Combine

apt-getcommands in a singleRUNand remove caches at the end - Combine

pipcommands in a singleRUNrun and make sure that the pip cache is removed

Pushing the image#

Once you are happy with your image and you want to use it on another machine, you will need to push it out to a registry. Otherwise, you will not be able to use the image on another machine without having to re-build it (therefore defeating the purpose of reusable images).

For pushing an image, there are typically two sub-commands that come into play:

When building images locally, as we did above, the name is fairly irrelevant (pytorchtest).

However, when pushing an image to a registry (docker hub or your own), then

naming (aka tagging) an image requires a bit more thought. Assuming that you have

a user account on docker hub called user1234, then you could name your image like this:

user1234/pytorchtest:pytorch1.6.0-cuda10.1-cudnn7-devel-0.0.1

That way, you still keep using your local image name pytorchtest, but you also

include the version of PyTorch, CUDA and cuDNN. The 0.0.1 at the end, is the actual

version of your image.

In order to push the image pytorchtest out to docker hub, you first need to give it

the proper tag:

docker tag \

pytorchtest \

user1234/pytorchtest:pytorch1.6.0-cuda10.1-cudnn7-devel-0.0.1

And for pushing it out, use this command:

docker push user1234/pytorchtest:pytorch1.6.0-cuda10.1-cudnn7-devel-0.0.1

Once the push is complete, you will find this image at the following URL:

https://hub.docker.com/u/user1234

Depending on the number of images you have, you may have to search for the

pytorchtest:pytorch1.6.0-cuda10.1-cudnn7-devel-0.0.1 tag.